"Order 150mg norpace amex, symptoms zinc poisoning".

By: Z. Goran, M.B. B.A.O., M.B.B.Ch., Ph.D.

Clinical Director, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Paul L. Foster School of Medicine

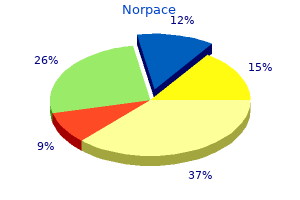

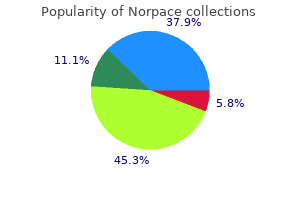

Mitoses within the marginal zone cell population range from 0-2 in a single high power field symptoms tonsillitis order cheapest norpace. The disease can present as an incidental finding or with symptoms of splenomegaly treatment 1 degree burn buy norpace 150mg visa. Other factors such as lymph node involvement shakira medicine generic 100 mg norpace with mastercard, hemoabdomen, a d j u v a n t chemotherapy, and c o n c u r r e n t malignancies did not influence 1-2. Spleen, dog: the neoplasm consists mainly of marginal zone cells which are intermediate in size (nuclei approximately 1. The neoplastic marginal zone lymphocytes are intermediate in size, with nuclei measuring approximately 1. Therefore, immunophenotyping and molecular clonality are ultimately required for a definitive diagnosis. The fields in which there were up to 2 mitotic figures further supported this diagnosis, and is likely indicative of later stages of disease development, as mitoses increase with disease progression. Similarly, the most likely reasons for false negative results in this case are mutation of gene segments that are not covered by the primer sets or mutation of primer sites during somatic hypermutation. In support of this suspicion is the fact that the IgH3 locus did not show a robust polyclonal curve as would be expected in a hyperplastic lesion, but instead had non-reproducible peaks of variable height within a weak polyclonal background. J P C D i a g n o s i s: v S p l e e n: Ly m p h o m a, intermediate size, low grade, consistent with marginal zone lymphoma. Conference Comment: the contributor provides an exceptional overview to splenic marginal zone lymphoma and discusses its diagnostic challenges, specifically in distinguishing from hyperplastic nodules. Splenic nodular hyperplasia is a common finding in dogs and presents with variable histologic appearance depending on its cellular constituents. The simple or lymphoid form of hyperplasia is composed of discrete lymphocytes often forming follicles with germinal centers. The complex form of nodular hyperplasia additionally contains a proliferative stroma. Some variations of these lesions were previously diagnosed as fibrohistiocytic nodules, and recent advances in immunohistochemistry has led to their reclassification into a diverse group of diseases to include the above hyperplastic nodules, histiocytic sarcoma, and various subtypes of lymphoma. Diagnosis of canine lymphoid neoplasia using clonal rearrangements of antigen receptor genes. Histologic and immunohistochemical review of splenic fibrohistiocytic nodules in dogs. Splenic marginal zone Bcell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathological and molecular entity: recent advances in ontogeny and classification. History: the dog was presented to the veterinary teaching hospital with inappetence, severe hepatomegaly and icterus. Bloodwork showed circulating lymphoblasts that were fragile and therefore often misshapen. Gross Pathologic Findings: the mucus membranes and internal organs were moderately icteric. The liver and spleen were both markedly enlarged (2 and 3 times normal weight, respectively). The stomach contained a large blood clot and several gastric ulcers were identified. The mass was composed of round lymphoid cells arranged in sheets and supported by a delicate fibrovascular stroma. The neoplastic cells had distinct margins with scant to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei were round to pleomorphic, had a finely clumped chromatin pattern, and 1 to 2 nucleoli. The nuclear diameter of the neoplastic cells was equal to the diameter of two regional erythrocytes. Lungs: Within the lumen of some of the smallsize pulmonary arteries, there were clusters of neoplastic lymphoid cells and karyorrhectic debris. Neoplastic infiltrates were also present in the bone marrow, liver, heart and multiple visceral lymph nodes (not shown). Peripheral blood, dog: A blood smear showed circulating lymphoblasts that were fragile and therefore often misshapen. Spleen, dog: Normal architecture is replaced by coalescing nodules of lymphocytes. Lung, dog: Neoplastic lymphocytes are present within moderate numbers with pulmonary capillaries.

Culling heavily diseased individual bats or populations was also proposed symptoms pancreatic cancer generic norpace 150mg on-line, but disease models suggest this approach may not be effective (Hallam and McCracken 2010) medications osteoporosis norpace 100 mg online. Management of amphibian chytridiomycosis may involve several activities which include environmental manipulation treatment urticaria buy norpace 100mg with visa, controlling amphibian introductions, and deploying ex situ conservation efforts to reduce the disease-causing bacteria in the environment and on hosts or to increase population buffering capacity (Scheele et al. Four of five studies found that increasing water temperature eliminated infection from amphibians (Sutherland et al. Such disturbances, depending on their severity or frequency, increase the likelihood of invasion by non-native plants (Haeussler et al. Defining light and competition levels (and corresponding harvesting and burn frequencies) that will promote regeneration of native species but deter invasion of non-native species is needed for all forest types. Invasion by non-native plants may occur primarily from unsustainable land management practices that have resulted in a seed bank depleted of native seed and the loss of native plant species because they are the most merchantable or most preferred by herbivores such as deer (Cervidae) or cattle(Bos taurus) (Beauchamp et al. Likewise, overgrazing by cattle and sheep (Ovis aries) may be prevented by rotating sites used for pasture and by fencing these pastures. Abandoned grazing areas that were overgrazed often become an epicenter for new plant invasions. Depending on the condition of the site and the type of grazer, simply removing the animals may not prevent invasions. For example, adding goats has proven to be effective at controlling several invasive plants, and removing goats has been detrimental to some systems (Zavaleta et al. Conversely, removal of feral sheep and cattle from Santa Cruz Island (beginning in 1981, with full eradication thought to have been achieved by 1997) initially resulted in increases in exotic fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and yellow star-thistle and only a slight increase in one of the native species (Klinger et al. However, passive recovery 28 years after the removal of the feral sheep from Santa Cruz Island shows a transition from non-native plants to native woody vegetation (Beltran et al. Changes in logging severity, fire intensity or frequency, or grazing pressure should incorporate best management practices practices aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive plant propagules. Plant propagules may be reintroduced via contaminated equipment used in a previous harvest or burn (Bryson and Carter 2004; Westbrooks 1998), transport of seed in animal dung via animal rotations from contaminated pastures (Bartuszevige and Endress 2008), and use of contaminated hay as forage (Bryson and Carter 2004; Westbrooks 1998) or gravel for road cover (Christen and Matlack 2009; Mortensen et al. Smothering or shading with mats or bottom barrier materials can be used to control smaller patches of invasive aquatic plants such as yellow floating heart (Nymphoides peltata) (DiTomaso et al. Mechanical removal of aquatic invasive plants (see Haller 2014) can be achieved by deploying boats with skimmers to remove surface-growing plants such as hyacinth (Hyacinthus spp. Draining wetlands or reducing water levels is one approach used for both plants and animals (Hine et al. Reducing wetland levels before summer or prior to extreme winter conditions can expose unwanted plants. Similarly, horticultural oil or insecticidal soap sprays have been found to be effective in reducing hemlock woolly adelgid populations on accessible trees but are not practical at the forest landscape level (Cowles and Cheah 2002; McClure 1995). Systemic insecticides are generally ineffective in controlling ambrosia beetles such as shot hole borer and redbay ambrosia beetle; however, prophylactic spraying of bark may help prevent attacks on individual trees (Peсa et al. Contact insecticides applied as a bark drench have been evaluated for controlling the crawler stage of balsam woolly adelgid (Adelges piceae) but must thoroughly drench the insect which is fairly well hidden on the tree, so it is not feasible for aerial spray or broad forest application (Ragenovich and Mitchell 2006). Use of pesticides against invasive pathogens of trees and other plants is not common in forests and wildlands. Rather, they are used on a small spatial scale within higher-value landscapes where economics or other values justify its use. For example, the systemic fungicide potassium phosphite has been widely used in California on high-value landscape trees as a bark spray (with or without a bark penetrant) applied to lower trunks of Quercus species to suppress sudden oak death development in trees newly infected with P. In a current long-term study, potassium phosphite is being evaluated for its potential to protect tanoaks from P. This treatment has also demonstrated efficacy in protecting avocado, pineapple (Ananas comosus), and cocoa (Theobroma cacao L. Yellow star-thistle has developed resistance to four auxin inhibitors, including triclopyr (Miller et al. Invasive plants that produce numerous seeds or spores and have long-distance dispersal are most likely to develop herbicide resistance after repeated applications. The acceptable number of herbicide applications requires a delicate balance between reducing the abundance of the non-native species and ensuring that treatments do not eliminate native species. Ideally, applied research should be combined with basic ecological assessments such as competition and demographic studies to define optimal application rates and timing of treatments. Acetaminophen baits have been shown to be effective for controlling brown treesnakes (Boiga irregularis; Savarie et al. The disease affects nonurban wildlife including the endangered black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), an obligate predator of highly plague-susceptible prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.

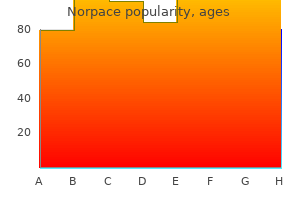

Can J For Res 38:12671274 Hata K treatment low blood pressure cheap norpace 150mg with amex, Kawakami K treatment effect generic norpace 100 mg free shipping, Kachi N (2015) Higher soil water availability after removal of a dominant treatment west nile virus 150 mg norpace for sale, nonnative tree (Casuarina equisetifolia Forst. New Phytol 203:110124 van Kleunen M, Weber E, Fischer M (2010) A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Funct Ecol 30:206214 Zavaleta E (2000) the economic value of controlling an invasive shrub. Temperature increases have been greater in winter than in summer, and there is a tendency for these increases to be manifested mainly by changes in minimum (nighttime low) temperatures (Kukla and Karl 1993). Furthermore, climate change may challenge the way we perceive and consider nonnative invasive species, as impacts to some will change and others will remain unaffected; other nonnative species are likely to become invasive; and native species are likely to shift their geographic ranges into novel habitats. Climate variables are known to influence the presence, absence, distribution, reproductive success, and survival of both native and nonnative species. Also, the availability of "empty" niches in the naturalized range, an escape from natural enemies, and a capacity to adapt to new habitats can S. Our chapter offers examples of biological responses, distributional changes, and impacts of invasive species in relation to climate change and describes how these vary among plants, insects, and pathogens, as well as by species, and by type and extent of change. Our assessment of the literature reveals that, for a given invasive species at a given location, the consequences of climate change depend on (1) direct effects of altered climate on individuals, (2) indirect effects that alter resource availability and interactions with other species, and (3) other factors such as human influences that may alter the environment for an invasive species. Conversely, elevated temperatures also have the potential to affect invasive insects negatively by disrupting their synchrony with their hosts and altering their overwintering environments. Our chapter provides information on how host-invasive species relationships and trophic interactions can be modified by climate change while recognizing that important knowledge gaps remain and need to be addressed. Similarly, management practices implemented in response to effects of disturbances and climate can alter the susceptibility to invasions in positive or negative directions (Chapter 7). For example, reseeding a disturbed area after a climaterelated event with seed contaminated with an aggressive invasive plant like cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) can unintentionally promote its spread. Climate change and invasive species are drivers of global environmental change that interact across biological communities in ways that have eco-evolutionary consequences. Rapid adaptation to local climates can facilitate range expansions of invasive species (Colautti and Barrett 2013), even beyond the climatic distributions in their native ranges (Petitpierre et al. Insect and disease outbreaks can affect ecosystemlevel carbon cycling and storage by reducing growth, survival, or distribution of trees. Under climate change, invasive organisms are likely to vary in their impact and rate of spread, depending on their sensitivities to climate variation and on the extent and type of climate change. In order to manage invasive species under a changing climate, it is important to anticipate which species will spread to new habitats and when, and to understand how the characteristics of specific invaders may disrupt or have the potential to disrupt invaded ecosystems. Of utmost importance in containing the spread of invasive species, managers must have the ability to (1) predict which species will positively respond to climate change, (2) predict and detect sites likely to be invaded, and (3) deter incipient invasions before they are beyond control. We outline methods for developing the capability to predict and monitor invasive species in order to forecast their spread and increase their detection. The basic approach to predicting the potential geographic distribution of invasive species in their naturalized range involves developing statistical models that describe their native range in relation to climatic variables (their climatic niche) and then applying the models to the naturalized range (Broennimann and Guisan 2008; Early and Sax 2014; Jeschke and Strayer 2008). The ability to predict the future distribution of invasive species in response to climate change is a complicated task, considering that numerous factors influence local and short-term patterns of invasion (Mainali et al. At the broadest level, climate change may create conditions that favor the introduction of new invasive species into habitats where suitability was improved while altering local distribution and abundance of existing invasive species (Hellmann et al. Climate change is also likely to modify competitive interactions, resulting in native communities that are more or less susceptible to colonization by new invaders or expansion by established invaders. If the competitive ability of primary invaders is lessened by climate change, the ecological and economic impact of the invader may be reduced to the point where it would no longer be considered invasive (Bellard et al. Conversely, climate change-induced interchange of biotic interactions may also expedite the conversion of benign, resident nonindigenous species to invaders (Richardson et al. Climate change could also facilitate the increased abundance of secondary invaders by reducing the competitive ability of the primary invader or by altering the effectiveness of management strategies (Pearson et al. The significance of secondary invasions is increasingly being recognized, and it may arise either from invasive species subordinate to primary invaders (Pearson et al. Collectively, if climate change increases the abundance and distribution of some invasive species while decreasing or converting others, the net result may be no change in species richness of either invasive or nonnative species (Hellmann et al. Many existing and potential invasive species spread into new areas as stowaways in and on cargo ships (in cargo holds, containers, or ballast water; as contaminants in agricultural crops; or on ships hulls) (Hulme 2009). In the United States, current inspection of cargo ships for invasive species involves examining a small percentage of cargo imports for a small subset of federally listed species while leaving the vast majority unchecked; some of these overlooked species could potentially become invaders under a scenario facilitated by climate change (Lehan et al.

Accordingly section 8 medications order norpace 150 mg with mastercard, plant traits that favor increased local abundance are key to medications knowledge buy 150 mg norpace otc driving local impacts such as clonality treatment for plantar fasciitis buy norpace online pills, resource reallocation to larger body size, and/or release from natural enemies (Blossey and Nцtzold 1995; Pysek and Richardson 2008; Rejmбnek 1996; Suda et al. Furthermore, traits linked to spread, such as increased fecundity and dispersal, facilitate the dissemination of those impacts over larger spatial scales only for species that can achieve high local abundance (Pearson et al. In this regard, plants are unique in that polyploidy events (the nuclear accumulation of multiple sets of chromosomes) are not always fatal (as they are in animals) and can be associated with the development of traits such as larger body size or increased seed production. Historically, analyses attempting to predict invader impacts based on plant traits alone have met with limited success (Pysek et al. However, distinguishing between traits associated with invasiveness (the effectiveness of the invader at establishing populations over wide areas) versus impact (the actual effect of the Invasive plants impact native terrestrial systems by altering species abundances and distributions, fire regimes, belowground biotic and abiotic processes, and resource availability to other taxa. By disrupting these basic processes, invasive plants can restructure extant ecological interactions and alter future trajectories of the community (Didham et al. According to competition theory, the plant predicted to win in head-tohead resource competition will be the species that can utilize a limiting resource at lower resource levels than its competitor (Tilman 1982). Different life history strategies and associated trait sets will generate costbenefit tradeoffs that favor different individuals or species under different resource and environmental conditions (Grime 1988). We need to better understand how limiting resources affect invasive plant impacts on natives particularly in the context of human-caused environmental change to understand and predict the effects of invasions in the context of directional anthropogenic change. In such a scenario, the success of the plant invader is often attributed more to ruderal traits associated with establishment as compared to competitive traits (ideal weed hypothesis, Baker and Stebbins 1965; Rejmбnek and Richardson 1996). The resulting lack of low- to moderate-intensity fires has led to population reductions for a federally endangered keystone species, the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), whose burrows serve as shelter for more than 330 other animal species (Van Lear et al. Plant invasions in this system contribute to thick understories, outcompeting fireadapted native plant species, displacing or extirpating species like the gopher tortoise, and altering the vertical and trophic structure, negatively impacting the system. Allelopathy, the chemical inhibition of one species by another, is another means by which invasive plants can directly impact native plants (Callaway and Aschehoug 2000). However, studies demonstrating allelopathic effects of invasive plants in natural conditions are uncommon (Hierro and Callaway 2003), and more definitive work is required to understand how this mechanism functions and the degree to which it can explain invasive plant impacts (Blair et al. Invasive plants can differ substantially in litter production and decomposition rates from natives due to differences in growth rates and tissue composition (Allison and Vitousek 2004; Holly et al. For example, cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) is a well-established and widespread invasive grass across the southern Gulf Coast, and now Atlantic States, due to multiple introductions with a proportionally high degree of introduced genetic variation and intrinsic phenotypic plasticity (Lucardi et al. Annual Cover (%) 0 - 10 11 - 25 26 - 50 51 - 75 76 - 100 Cedar City Reno Ely Elko Salt Lake City Las Vegas 0 105 210 km N. These species can also dry out earlier in the season than native plants, creating a dangerous fire hazard. At fine spatial scales, cheatgrass establishment in areas with cheatgrass in the vicinity is correlated with burn extent (Kerns and Day 2017). The "grass-fire" cycle can drive an ecosystem further from its original state and may eventually lead to a novel ecosystem that has no historical analog (Box 2. Increased fire occurrence, intensity, and severity have been observed in association with these types of grass invasions across the globe (Balch et al. For example, one fire history study in Idaho estimated a fire return interval of 35 years in cheatgrass-dominated rangelands, compared with 60100 years in native sagebrush (Artemisia spp. Plantsoil feedbacks are an important indirect interaction by which invasive plants impact native plants. Plantsoil interactions can result in positive or negative feedbacks between plants and soil microbial communities (Wolfe and Klironomos 2005). For instance, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolate) is nonmycorrhizal and may impact natives by depleting mycorrhizal inoculum to the detriment of native host plants (Stinson et al. Emergent risks of habitat degradation due to invasive-dominated grasslands that readily burn are now widely recognized. Cheatgrass invasion and the grass-fire cycle are now known to be one of the primary mechanisms altering contemporary sagebrush (Artemisia spp. Much of the Great Basin has been invaded to some extent by annual grasses such as species in the genus Bromus, medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae), and ventenata (Ventenata dubia). Much of the sagebrush biome is home to the greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), a large gallinaceous bird that requires distinct sagebrush habitats to survive. As part of this strategy, a science framework for conservation and restoration of the sagebrush biome (Part 1) was recently released (Chambers et al. Restoration of cheatgrass-dominated landscapes in the sagebrush biome emphasizes resilience to wildfire and resistance to cheatgrass invasion.

The expectations of equality which they have at least to medicine on airplanes order norpace some extent internalized symptoms low blood pressure buy norpace 150 mg cheap, so that they form part of their self-image medications beta blockers order norpace on line, are now contradicted by experiences of inequality both at work and in private life. Already in the 1980s a number of studies of young people were predicting the conflict we have just outlined. Klaus Allerbeck and Wendy Hoag, for example, wrote: When a girl chooses a job that is stimulating and interesting. Even if some room for manoeuvre is present in the family, different laws prevail in the labour market. One of the questions they were asked was how each partner would like to change and how each thought the other partner should change. Whereas the women mostly wanted to be more emancipated than they already considered themselves, the men wanted their partner to be less emancipated than she actually was, to be a more traditional wife. Nevertheless, `the wishes for change turn out to be rather meagre (that is, the differences between self-image and desired ideal are minimal). On the basis of what has been outlined, it may be assumed that this modernization trap affects women in particular. The male partner from whom she hopes to receive closeness and support displays attitudes and modes of behaviour which violate her understanding of a fair division of labour and equality of opportunity; he takes privileges for himself and leaves her with most of the burdens. For many women today, such conduct means not only a lack of help in everyday life but also, I would argue, a daily experience of inequality within the family, an offence against expectations and demands that are part of their life project, a display of contempt for their personality and indeed for their existential desires and rights. The available studies suggest that such disappointed expectations give rise to rancour against husbands and dissatisfaction with marriage and the family (Hochschild, 1990; Rerrich, 1991a). With a subjective sense that they have something to lose, men feel troubled and pressured by women (Erler et al. For both sexes, then, the issue of the household division of labour stirs much deeper layers of identity, planning for the future, and self-esteem. The resulting thesis is that when conflicts flare up in marriage or a relationship over the division of labour, more than housework is at issue. Both also stand for ideas of what a family and a relationship between the sexes should be like. No doubt it is mainly women who bring such identity questions into a relationship. But their conflict potential and their characteristic intertwining of division of labour and identity has an exemplary character, as Giddens has shown in his Modernity and Self-Identity (1991). According to Giddens, the scope for decision that opens up in late modernity not only concerns external questions but increasingly also matters of identity. At many levels of everyday life, including small details and all the things that used to be determined by routine and tradition, we are now faced with decisions about who we are and how we want to be. Identity in late modernity is less and less an ascribed fate; it becomes dependent upon decision, risky and reflexive. More, their very sharpness and bitterness comes from the fact that they are part of an ongoing identity struggle which always breaks out when external barriers and constraints become more fragile, when individuals are permitted, expected and compelled to shape the definition of themselves. Even today marriages (with or without a certificate) are not merely work communities; they are not just a question of who takes the rubbish down or washes the floor. Precisely today, there are quite different measures, criteria and expectations 105 Individualization bound up with living together all the desires, for example, which arise out of the experiences of an individualized society, from the quest for security and inner stability to the secular religion of love (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim, 1990). It is therefore quite conceivable that, even among women with strong expectations of equality who get little support from their man around the house, a strong potential for conflict will not necessarily build up. This might be the case if they are very content in other areas of the marriage, if their partner has many other qualities that they value or regard as compensation (reliability or tenderness, a sense of humour, a number of shared interests, and so on). We may assume, however, that such cases are likely to be rather rare in the long term. For if we look more closely at the social script for marriage in the individualized society, it becomes apparent at many points that it involves a kind of dual script: expectations of feelings and expectations of equality, whose combination can easily become like the squaring of a circle (Beck and BeckGernsheim, 1990). When things are not going well with the division of labour, her feelings of love are also disturbed; and conversely, when the man does his share in the house, this is recognized by the woman and interpreted as a sign of love (Thompson, 1991: 185). Hochschild spends a whole chapter on the story of Evan and Nancy to illustrate the tensions in modern marriage. In the milieu of technical staff (ten interviewees, four of them women), a far-reaching division of labour with partners was found. One woman, whose partner did half the housework, said: `I really know where I am with my partner.

Cheap norpace 100 mg otc. न्यूमोनिया के 3 घरेलू इलाजलक्षण Pneumonia 3 Home Remedies Treatment And Symptoms.